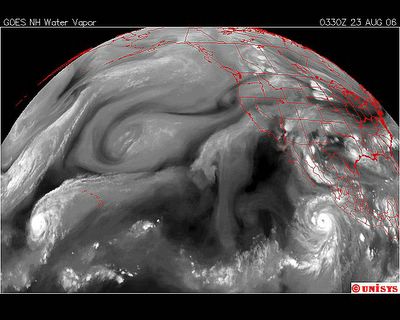

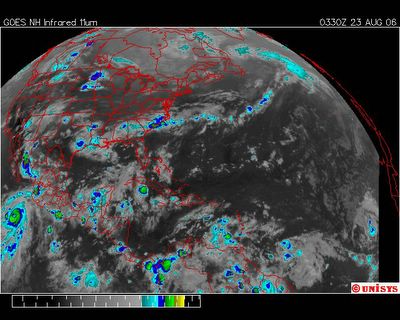

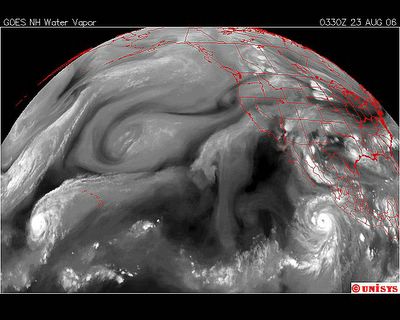

August 23, 2006. 0330z. Water Vapor GOES West Satellite.IOKE is in a very odd position in the Pacific. The storms of the Pacific don't start near Hawaii. Hawaii is a land mass. It's warmer than the ocean. No different than the storms that start near Mexico all the time. The aire is hotter there. Hawaii is a volcanic sea chain. It's small in mass. I find it very unusual to have a storm BEGINNING there. It indicates to me the extreme heat of the Northern Hemisphere. The 'tail' of IOKE extends northeast. This is very similar to a storm that existed in the Atlantic last year. That storm was Wima (click on). As soon as Wilma hit the open water it turned into the vortex it was attached to and head straight into it. I probably have a satellite picture on this blog that illustrates that. Wilma at it's strongest was a Cat 5 with the lowest millibars of central pressure of any Atlantic storm, 802 mbar. Katrina was 902 mbar. Wilma started on October 15 and continued through the 25th, ultimately causing a total of 61 deaths of which 36 were in Florida. But to get back to the Atlantic storms. Every major storm in the Atlantic is accompanied by one in the Pacific. That is occurring now with Ileana. Currentlly Ileana is moving quickly north but as a rule when there is a major Atlantic storm heading to land, the Pacific storm lingers in a position that seems to support 'the path' of the Atlantic storm. That has been my experience in recent years in observing these stroms.

August 23, 2006. 0330z. Water Vapor GOES West Satellite.IOKE is in a very odd position in the Pacific. The storms of the Pacific don't start near Hawaii. Hawaii is a land mass. It's warmer than the ocean. No different than the storms that start near Mexico all the time. The aire is hotter there. Hawaii is a volcanic sea chain. It's small in mass. I find it very unusual to have a storm BEGINNING there. It indicates to me the extreme heat of the Northern Hemisphere. The 'tail' of IOKE extends northeast. This is very similar to a storm that existed in the Atlantic last year. That storm was Wima (click on). As soon as Wilma hit the open water it turned into the vortex it was attached to and head straight into it. I probably have a satellite picture on this blog that illustrates that. Wilma at it's strongest was a Cat 5 with the lowest millibars of central pressure of any Atlantic storm, 802 mbar. Katrina was 902 mbar. Wilma started on October 15 and continued through the 25th, ultimately causing a total of 61 deaths of which 36 were in Florida. But to get back to the Atlantic storms. Every major storm in the Atlantic is accompanied by one in the Pacific. That is occurring now with Ileana. Currentlly Ileana is moving quickly north but as a rule when there is a major Atlantic storm heading to land, the Pacific storm lingers in a position that seems to support 'the path' of the Atlantic storm. That has been my experience in recent years in observing these stroms. In realizing that, and that there is more turbulence off Africa resulting in another excalating storm I have to wonder what storm will follow Ileana. Not only that BUT, Ileana is also a part of a larger system noted above .

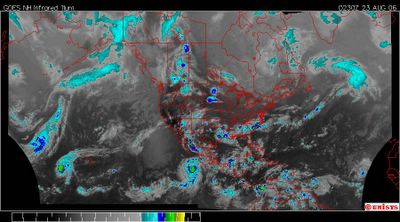

Now, additionally, there has been a lot of turbulence in the Carribean Sea as well.

Satellite below.